|

Contents

(Within the text click a heading to return here)

The Consultant

Voice Communication

Base Caps

Mesh Grids

Filaments

Gas Control

Captain Henry Round was never (disputed fact- Ed.) a full-time employee of Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company (later The Marconi Company) but he was one of their leading consultants over the period 1910-30, specialising in the design of valve sets and the valves for them. One of his most important contributions was the concept of designing valves to meet particular requirements rather than inventing new types of valve and expecting other people to find a uses for them.

Captain Round's valve designs look rather strange to us but they make perfect sense when you know something about the type of set he was designing to use these valves and the applications for which they were intended. His valves are in fact extremely efficient when used as he designed.

The Marconi Company was concerned to maintain a world lead in wireless communication. It was never seriously interested in broadcasting or consumer markets: world-class performance was essential, quantities were small, the manufacturing cost per individual valve was negligible in comparison with what was at stake.

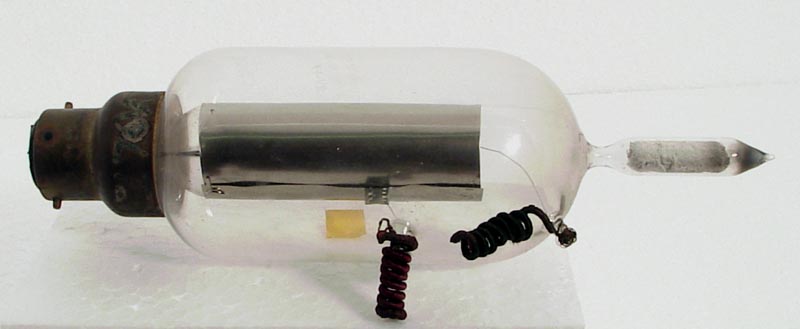

Captain Round's early valves were designed for performance, not for mass production. Up to around 1919 they were handmade by craftsmen in the Research Department of the Ediswan Lamp Works. The term 'Round Valve' normally applies only to the early types which looked similar to the Type N above. These notes apply only to these early types all of which were soft valves, i.e. deliberately gas-filled at very low pressure.

Because the all Round's earlier types were intended for in-house use by the Marconi Company or for specialist military applications during WW1, they were never marketed in their own right and no sales leaflets or data sheets exist, as far as we know. Indeed, most technical details were cloaked in commercial and military secrecy. Much of the information now available is hearsay originating from the memories of Marconi veterans. To this we can add what we can glean by closely examining surviving examples of the valves themselves and the sets they worked in. Other sources include Captain Round's patents and surviving user instructions for some of his sets. But much research remains to be done.

Around 1910 Captain Round began work to develop wireless telephone (voice) communication using triode valves, Marconi's had been using Fleming diodes for some years. Similar work was under way in Germany (of which Round was aware) and in the US. However, it is not clear what, if anything, Round knew of the American work. By 1912 he had not only designed a sea-going table-top transceiver giving good voice communication over ranges up to 50 km, plus the valves to go in them (2 types) but had successfully organised substantial production batches of these.

Hearsay has it that Round exceeded his authority (as a consultant) in authorising production of valves and sets without the Directors' consent, which he knew was unlikely to be given. However, the sets were technically successful and immediately popular with customers (owners of medium-sized coastal and fishing fleets) who wanted to keep in touch with their ships without the expense of employing a large number of morse-trained Radio Officers. Marconi's made good profits from the sets and Round was forgiven.

These early sets used one receiving valve (Type C(?), externally identical to the Type N above) and one transmitting valve (Type T(?), which was considerably larger). Captain Round continued to design further, improved sets. In accordance with his policy of matching the valve characteristics to the application, by 1915-16 there were at least 4 varieties of receiving valve (Types C, D, CA and N) and at least 3 varieties of transmitting valve (assuming that Type NT was distinct from the well-known Type TN).

Here we consider only the 4 receiving types which seem to have been made and used in some quantity. All 4 types are externally similar (to Type N) except for their base cap arrangements. Some valves are fitted with a bayonet, some with an Edison screw cap, and some with (probably a bayonet cap) sheathed in a black ebonite tubular case (either large or small diameter) with 4 side contacts.

Interestingly, the type of base cap seems to bear no correspondence with the type number marked on a valve. For example, the Type N is also to be found with an Edison screw cap fitted. The real differences between the 4 types seem to relate to grid mesh, type of filament and (probably) also to the gas filling. Which we cannot, of course, assess merely by external examination.

One of Captain Round's design principles was that the grid mesh should entirely surround the filament, leaving no path for an anode-to-cathode arc through the ionised gas filling. The grid mesh was a stiff self-standing structure whose lower end was locked over a glass stem in the same manner in which the self-standing anode can be seen to be locked over a larger glass stem. The top end of the grid was domed so that it fully enclosed the filament assembly. This design feature (which Round patented) is essential to the successful use of gas-filled amplifying valves at high anode voltages. Indeed, it was so successful that Round perpetuated the concept of total filament enclosure in his early designs for high-vacuum valves such as the Type Q. This is probably why such valves were successful in the early days (c. 1916) when it was hard to get a really good vacuum on the production line.

Although all the receiving 'Round Valves' we have seen have the same grid construction and support arrangements, they do seem to have two quite different grades of grid mesh, coarse and fine. Types D and N have grids of fine wire mesh while the other types have grid mesh of thicker wire. Paper labels on my Type Ns indicate that the optimum anode voltage was 70 to 75 volts. Some N's have shiny (possibly nickel) anodes (see photo) but others have dull anodes.

Most receiving Round Valves, including the Type N, have filaments of fairly thick platinum wire coated with lime and operated at bright red heat. This is an early form of oxide-coated filament (lime = calcium oxide) which was comparatively easy to make since lime is non-poisonous, stable in air, and sticks well to metal (as kettle owners know). Later oxide-coated filaments used barium and strontium in addition to calcium; they were more efficient emitters than lime alone but delicate and difficult in several respects. The Type N filament is in the form of a single, self-supporting, inverted V. Making the filament thick enough to support itself avoids problems with supports sprung to accommodate thermal expansion but it does mean that the filament has a low resistance and consumes several amps, typically at around 2V.

Some types of Round valve, especially the transmitting types, had up to three such filaments with provision to use them singly if required. This explains why some valves are fitted with 4-contact base cap sheaths.

It is not easy to see the filaments in the coarse-mesh types. Most are of the lime-coated platinum type but possibly of different thickness (i.e. current rating). However, one of my specimens (not a Type N) has a 'bright' filament (almost certainly tungsten) which seems to require 4 to 6V.

The partly-ionised gas filling of Round valves is crucial to correct operation. When used at high anode voltages, high-speed gas ions striking the surfaces of electrodes or the envelope tend to 'stick' (become adsorbed) so the quantity of free gas remaining in the valve (i.e. the gas pressure) falls. This upsets the proper operation of the valve. The asbestos 'pellet' in the tubulation at the top of the envelope contains 'spare' gas adsorbed within itself (asbestos has a very large micro-surface area and can adsorb seemingly prodigious quantities of gas). Heating the pellet (by heating the outside of the tubulation) causes a little of the 'spare' gas to be released into the valve. Conversely, when the valve is left cold and unused for long periods, some of the free gas may be re-adsorbed into the asbestos. Correct operation therefore depends on judicious warming of the tubulation.

Captain Round's sets were provided with a small solenoid-like heating coil which fitted over the tubulation and was heated from the filament battery controlled by a rheostat. The idea was to hold the pellet at just the right temperature for the asbestos to be in equilibrium with the desired correct free gas pressure. Hearsay says that operators discarded the heating coil because its response was too slow and used a lighted cigar instead.

Properly used by trained experts, Captain Round's early soft triode sets achieved amazing sensitivity and performance, not equalled by sets using high-vacuum valves until many years later. However, when demand increased during WW1 it was soon found that the average factory girl could not make the valves successfully and the average Tommy in the trenches did not know how to use them. Hence the famous, and greatly inferior, Type R.

|